In March of 1960, a group of scientists detonated three bombs of 130 kilos each in the southwest of Australia, off the coast of Perth. They wanted to see how far the sound could travel. For this, a station in Bermuda, just on the other side of the world would try to listen carefully to any sound that came to him.

They did not have much hope. They had already tried something similar and they had not succeeded. Therefore, the launching of the bombs had more to do with the fulfilment of the research plan than with the expectation that something would be heard in Bermuda. However, it was heard and only three and half hours later.

SOFAR (we have arrived)

But, to understand it correctly, we have to go back two decades. In 1943 and after years of spinning around, Maurice Ewing, a researcher at Columbia University, decided to test one of his theories: that low frequency waves, being less vulnerable to dispersion than high ones, should be able to travel great distances without too much trouble.

But, to understand it correctly, we have to go back two decades. In 1943 and after years of spinning around, Maurice Ewing, a researcher at Columbia University, decided to test one of his theories: that low frequency waves, being less vulnerable to dispersion than high ones, should be able to travel great distances without too much trouble.

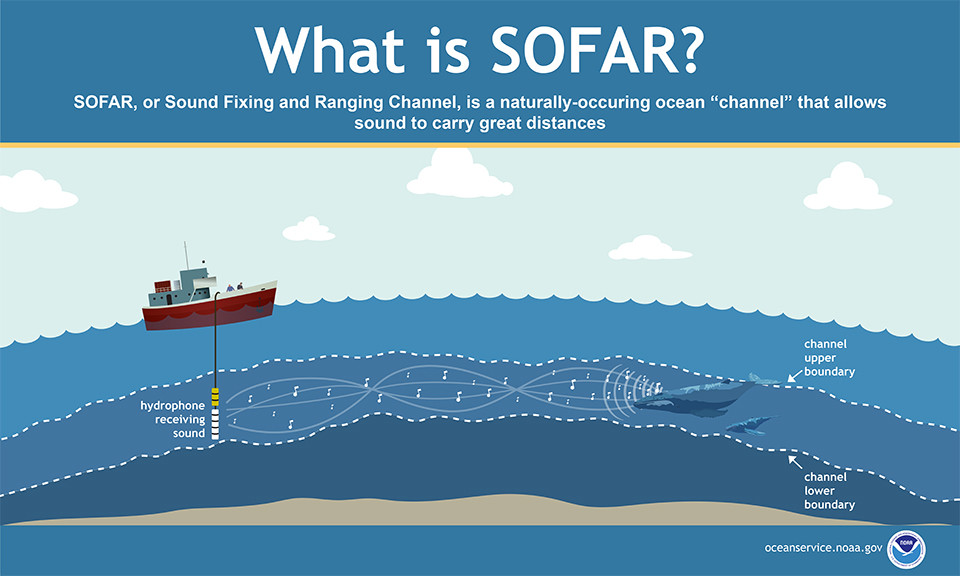

Together with J.L. Worzel, caused a TNT explosion into the water off the coast of the Bahamas and waited to see what happened. The signal, confirming Ewing’s theory, was detected without problems by receivers located in West Africa, 3,200 kilometres away. However, the test helped detect something else: around a kilometer deep, they found the SOFAR (Sound Fixing and Ranging channel) or “deep sound channel”.

Discovered independently by Leonid Brekhovskikh, a Russian researcher at the Lebedev Institute of Physics, while studying the explosions of the Sea of Japan, SOFAR is a thermodynamic phenomenon thanks to which “a sound introduced in this sound channel could travel thousands of kilometers horizontally with a minimal loss of the signal “.

The discovery of the SOFAR was very useful to design mechanisms with which to detect submarines. And for decades, we tried to understand well how the channel worked, because it was not always at the same depth and on what factors it depended.

An X-ray of the sea of the 60s

The Australian bomb experiment wanted to understand how the channel works on a planetary level. But perhaps the most interesting part of that experimental savage is what can tell us about the ocean, its temperature and its conditions, now, almost 60 years. To give us an idea, the speed at which sound travels through the ocean depends on its temperature. In that sense, if we can reconstruct what happened during those March hours, we will have an X-ray of that time.

The Australian bomb experiment wanted to understand how the channel works on a planetary level. But perhaps the most interesting part of that experimental savage is what can tell us about the ocean, its temperature and its conditions, now, almost 60 years. To give us an idea, the speed at which sound travels through the ocean depends on its temperature. In that sense, if we can reconstruct what happened during those March hours, we will have an X-ray of that time.

A few years ago, a researcher at the University of Washington, Brian Dushaw, spent a lot of time trying to reconstruct the details of the bomb throwing. We knew it happened on March 22 at 03:00 a.m. (local time), so Dushaw reconstructed the daily life of HMAS Diamantina using the annotations of the captain of the ship.

It has been hard to understand the curve of the Bahamas detector that we see at the top. In the end, this type of paleo oceanic research is starting, but it has the keys that will allow us to understand in depth the changes that climate change is producing. There is a lot to learn from history, that we do not forget.